Leadership lessons

Black business leaders offer wisdom, advice for next generation

Kate Andrews //January 29, 2021//

Leadership lessons

Black business leaders offer wisdom, advice for next generation

Kate Andrews //January 29, 2021//

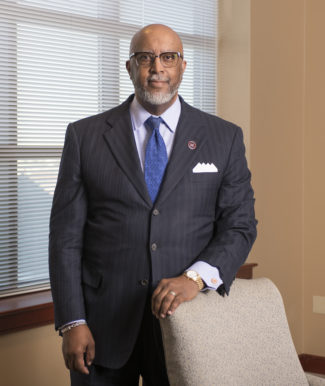

Warren Thompson got his start as an entrepreneur at age 16, buying out his family’s hog business. It was a sideline enterprise his father had started at their home in the Blue Ridge Mountains to supplement his income as a teacher.

Today, Thompson is the president and chairman of Reston-based Thompson Hospitality Corp., the nation’s largest minority-owned food and facilities management company.

He’s one of 13 Black business and nonprofit executives in Virginia who spoke to Virginia Business to offer insight into their own paths to success as well as advice for future Black business leaders — and people of all races who want to make their workplaces more inclusive, equitable and welcoming to employees of all backgrounds. Many spoke about the impact of the social justice protests that began in late May and early June 2020, after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

Some also talked about being intimidated early in their careers, often as the only Black person in a room full of powerful white men.

Not Thompson.

He was one of about a dozen Black students at the private, all-male Hampden-Sydney College in the late ’70s. “We planned to take over the school,” he says matter-of-factly.

Thompson and other Black students won school leadership roles, including newspaper editor, head of the science club and student government treasurer. They launched the minority student union, which raised money for literacy programs in Prince Edward County, where the public school system was shut down from 1959 to 1964, rather than integrating.

As an employee of Marriott Corp. after graduating from the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business in 1983, Thompson was an ambitious up-and-comer who managed the Roy Rogers Restaurants chain, which was then owned by the hotelier.

“I brought in a lot of money for them,” he says, and by the early ’90s, Thompson was ready to branch out on his own. After a few starts and stops, he was able to purchase 31 Big Boy restaurants, combining backing funding from Marriott with $100,000 of his own money.

“I always encourage young people, spend some time in that industry working for someone else,” Thompson says. “It becomes very, very difficult to break in and succeed [as an entrepreneur]. Earn your stripes, make mistakes on their dime. There’s very little room for error in those first five years [of business ownership] because you don’t have a lot of capital.”

In the years since its founding in 1992, Thompson Hospitality has expanded to include numerous restaurant brands. It also provides food service at companies, school systems, medical centers and universities across the country.

Despite his own success, Thompson acknowledges the continuing difficulty for many potential Black entrepreneurs to access capital and, equally, build generational wealth.

He tells a story: His father and a white acquaintance both graduated from college at the same time during the Jim Crow era. Both interviewed for a job at DuPont, where the white man was offered a corporate position at $5,000 a year, and Thompson’s father was offered a janitorial job for about $2,000 a year. He decided instead to teach, which paid about the same as the custodial position.

DuPont is now a client of Thompson Hospitality, he notes with a smile. But back then, “this was the way it was. … It’s during that time that generational wealth was created.” It’s an example of why there’s a continuing chasm between white and Black Americans in terms of homeownership and business ownership, he adds.

In 1950, Black men earned 51 cents for every dollar earned by white men; the wage gap remained the same in 2014, according to a 2020 study by economists from Yale and Duke universities.

Amid such alarming statistics, Virginia Business asked some of the state’s most successful Black business leaders to impart their wisdom and advice for the next generation of Black businesspeople.

ED BAINE

President, Dominion Energy Virginia

Named president of Dominion Energy Inc.’s Virginia operations last year, Baine grew up on a tobacco farm in Lunenburg County and attended Virginia Tech before joining the Richmond-based Fortune 500 utility as an engineer in 1995. Baine is encouraged by the increased awareness of racial inequity that’s taken place since last year, but cautions: “No one should believe that six months or even a year’s worth of work is ultimately going to counter” centuries of racism. “If you create a culture at a workplace where all are appreciated, everyone will benefit as well. That takes work, that takes resources, that takes behavior. If you give more people the ability to compete for a job for themselves and their families, a lot of things start to get better.”

GILBERT T. BLAND

Chairman, The Giljoy Group

A longtime Pizza Hut and Burger King franchise owner in Hampton Roads, Bland serves on several boards, including the Urban League of Hampton Roads, for which he serves as president and chairman. As a young man, Bland learned the importance of “preparation and knowledge of the industry. I spent a lifetime building relationships, [learning] not just how it benefits me but how it benefits others.” Even when meeting with someone for a loan or a partnership, “think in terms of what the other person needs,” he suggests. “If somebody is helping me reach a goal, I feel a lot differently when someone asks, ‘What can you do for me?’”

VICTOR BRANCH

Senior vice president and Richmond market president, Bank of America

A Dinwiddie County native, Branch started in the banking industry 37 years ago with Richmond-based Sovran Bank, which later became part of Bank of America. He’s a William & Mary graduate who serves on the university Board of Visitors. “My secret, if there is such a term, is trying to connect with my colleagues internally and trying to connect with my clients,” finding common objectives and goals, and “trying to build that bridge to trust,” Branch says. “One thing I told my teammates that worked for me is that I validate people. You acknowledge them as a human being. You learn their name. If it’s a difficult name, say the name correctly. Learn a little bit about them. Who is their favorite sports team? The running joke in Richmond is, ‘Who are their people?’ Ask them about themselves.”

VICTOR O. CARDWELL

Attorney and chairperson, Woods Rogers PLC

Cardwell is the new chair of the Virginia Bar Association’s Board of Governors and was previously deputy associate chief counsel for the U.S. Department of Labor Benefits Review Board. He says that to rid itself of structural and cultural racism, a workplace must “discuss it openly and honestly — not to blame, but to develop a multifaceted path forward. This is not easy to do. The historical impediment to Black success and wealth have been so ingrained in our culture that to have a fair conversation, we must look at the health care, housing, educational and judicial systems. We must consider the opportunities that were lost or never presented to generations of citizens.”

GLENN CARRINGTON

Dean, Norfolk State University School of Business

A longtime tax attorney who served in executive roles at Ernst & Young, the IRS and Arthur Andersen’s National Tax Office, Carrington came out of retirement in 2017 to serve as NSU’s business school dean. Because of his job, Carrington spends a lot of time with business students, who are required as freshman to write a “what I want to be when I graduate” essay, which he reads. To reach their goals, Carrington advises, “Get your three P’s down: perseverance, patience and professionalism. You’ll be tested. You’ve got to be ready for that test.” Mentors and other advisers have always meant a lot to Carrington, and he says that one of his aims is to bring back a more “hands-on” approach at NSU. “Someone has to put your name in the hat,” Carrington says. “A relationship doesn’t stop and start at the workplace. Clients hire people a lot of the time not only because they’re smart, but can they trust that person? Don’t underestimate relationships.”

DONNA GAMBRELL

President and CEO, Appalachian Community Capital

Gambrell has led the Christiansburg-based Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) since 2017 and previously oversaw the U.S. Treasury’s national CDFI Fund from 2007 to 2013 as the first and longest-serving Black woman to be its director. Gambrell says that — especially for women — “most of us grow up polite and professional” and sometimes are scared to speak up in large groups of important people. That needs to end, she says. “I’d encourage any Black leader to be bold, to talk about why this is necessary. This is what I tell people, if you’re looking for ways to be more racially sensitive, look first at your own organization. Do you have a racial inclusivity statement? Government can do that as well as private industry can. If you’re in the community, always look for minority suppliers, retail, etc. Always be thinking about how far you can go.”

JONATHAN P. HARMON

Chairman, McGuireWoods LLP

A West Point graduate, U.S. Army Gulf War veteran and respected litigator, Harmon became the first Black chairman at McGuireWoods, Virginia’s largest law firm, in 2017. Harmon’s mom died at the age of 46 when he was in college; both of his grandmothers died that same year. His father asked him to speak at his mother’s funeral, Harmon remembers. He didn’t know if he would make it through without breaking down. “That was the hardest time in my life,” Harmon says, but he realized that speaking in front of people was one of his gifts. “It was in that low moment, that’s when that flower popped up.” Even in the midst of grief, such as losses to COVID-19, he says, good things can sometimes develop.

D. JERMAINE JOHNSON

Greater Washington and Virginia regional president, PNC Bank

Johnson has worked in banking for 25 years, starting as a management trainee for Bank of America. Johnson, who was promoted to his new position in August 2020, advises young employees to “get really good at what you’re doing right now, but be open. Be willing to evolve.” As a college student, he decided that accounting was not for him and switched to a finance major after participating in an internship program. In part, he chose banking “because it has so many facets. I was hopeful that over time I’d find a passion. I think we all strive to do the things we’re passionate about … because we spend so much time at work.”

MAURICE A. JONES

President and CEO, Local Initiatives Support Corp. (LISC)

A former state secretary of commerce and trade, and deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development from 2012 to 2014, Jones was appointed CEO and president of LISC in 2016, one of the nation’s largest organizations supporting economic opportunity in financially distressed communities. Jones says that 2020 was “transformative” in terms of understanding structural racism and its impact on Black people’s lives. The challenge, he says, is “looking for ways to transform epiphany moments.” Jones urges Black-led organizations and businesses, as well as individuals, to make the most of the momentum. “Don’t play small ball now. Your ask now needs to be audacious and bold and long-term. The urgency of this moment will subside. Make sure that you ask big things of them.” Specifically, “impress upon people [the need] to commit now and engage in this kind of support for at least the next 10 years.”

J.D. MYERS II

Senior vice president and region manager of Virginia operations, Cox Communications Inc.

Myers, who grew up in a military family, served as a U.S. Army officer and then joined Cox Communications’ Virginia and North Carolina operations in 2006, first as Northern Virginia market leader and vice president of Cox Business. Like many leaders, Myers cites the importance of building relationships. “That doesn’t mean they have to become your best friends and your buddies,” but there’s a reason golfing may be a good pastime to pick up, he says. Also, “master the art of chit-chat.” Listen to talk radio, understand current events and what’s happening with the political climate, as well as what is trending in your industry. Myers also advises having a “meeting before the meeting,” talking with others and asking what they plan to bring up. If someone says something that “you know a little about,” Myers suggests the “co-sign technique,” saying that you agree with the colleague’s idea, while rephrasing it in a different way.

STACEY D. STEWART

President and CEO, March of Dimes Inc.

Stewart took the helm at Arlington-based March of Dimes in 2017 as the first Black person and second woman to lead the 83-year-old nonprofit devoted to improving maternal and infant health. She previously served as the U.S. president of United Way Worldwide and as president and CEO of the Fannie Mae Foundation. The daughter of a physician and a pharmacist, Stewart learned about leadership from her parents. “My father committed his time outside his practice to ensure that hospitals across the South were desegregated. … My mom served many years on Atlanta’s City Council before making an unsuccessful run for mayor in the 1990s,” Stewart says. “My parents were committed to their professional lives, but they taught me that leadership in your professional life isn’t enough, especially when your community needs you.” Early in her career, she “felt awkward and uncomfortable in meetings with my peers and higher-ups. A critical moment happened for me when my supervisor noticed and pulled me aside. He told me he hired me for a reason: my skills and expertise. He stressed the importance of speaking up in meetings and sharing my ideas.”

TAMIKA L. TREMAGLIO

Greater Washington managing principal, Deloitte

For the past four years, Tremaglio has led operations in the Washington, D.C., region for Deloitte, one of the Big Four accounting firms, where she has worked since 2010. She previously served in leadership roles at Huron Consulting Group and KPMG. Tremaglio recommends the PIE concept from Harvey Coleman’s book, “Empowering Yourself: The Organizational Game Revealed” — P for performance, I for image and E for exposure. “Most people, particularly Black professionals, are accustomed to spending copious amounts of their time on performance — working hard to be focused, responsive and technically proficient — but how do you continue to raise the bar and propel yourself to the next level? As you grow in your career, spending more time on your image (how you show up — not simply appearance, but do you appear confident and prepared?) and exposure (what experiences are you getting — what are you being exposed to?) becomes paramount.”

Related Articles

Talking shop

Black entrepreneurs, especially women, face extra challenges

Disrupting racism

Janice Underwood leads the state’s efforts to create a more equitable culture