Pipeline battle

Supporters say project is needed, but it faces stiff resistance

Pipeline battle

Supporters say project is needed, but it faces stiff resistance

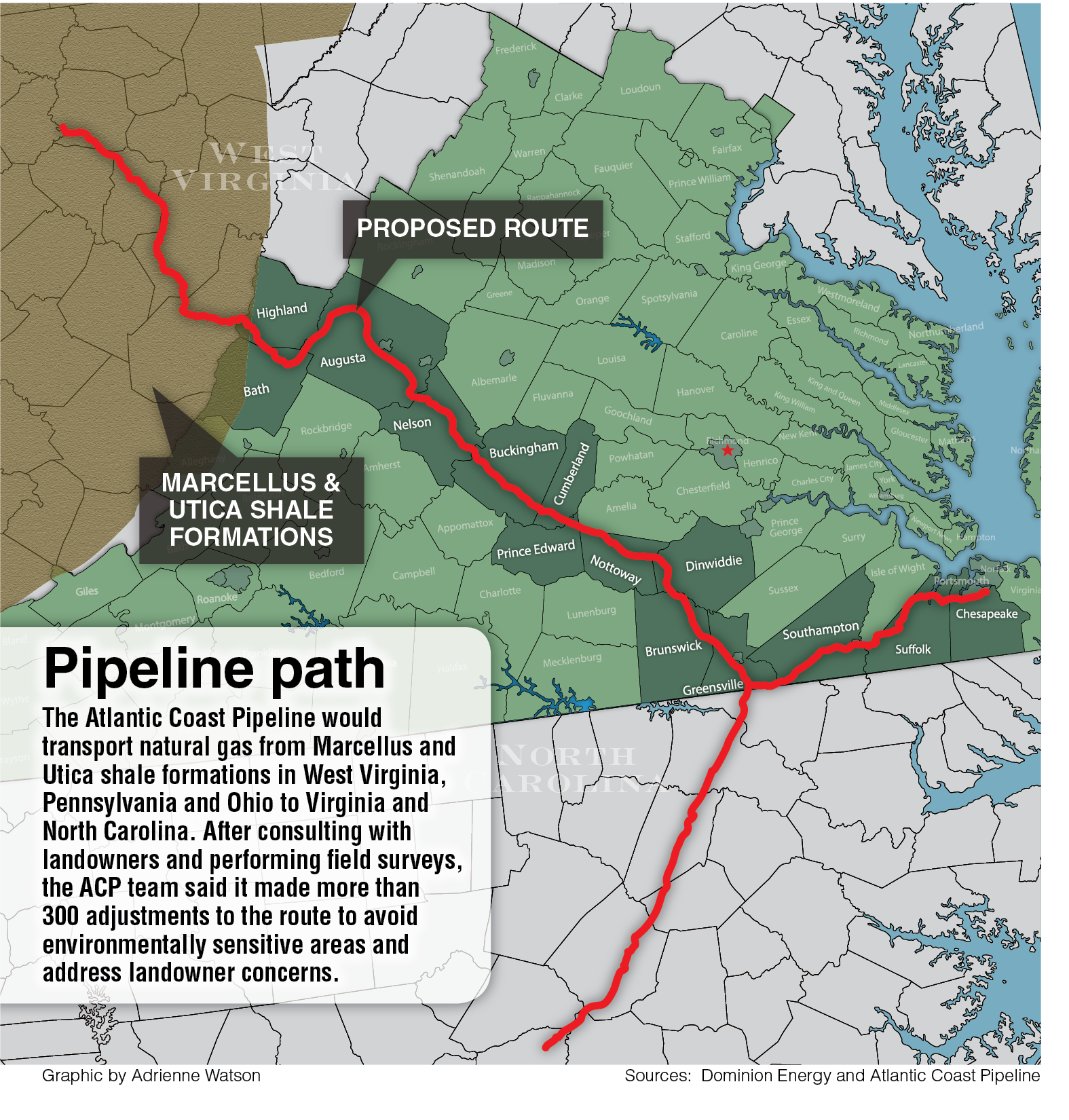

For nearly three years, a battle has raged in Virginia over the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. A massive and complex project, the 600-mile pipeline would tap into the rich shale fields of the Marcellus and Utica Basins and transport fracked natural gas to utilities in Virginia and North Carolina.

The proposed interstate pipeline, stretching from West Virginia through parts of Virginia and to eastern North Carolina, has drawn broad business support and vociferous opposition.

Anti-pipeline demonstrators have staged protests from rural Nelson County to the halls of Virginia’s Capitol. They have stormed the General Assembly, the annual meetings of Dominion Energy and more recently the victory party of Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam after his win in June’s Democratic gubernatorial primary.

Interested parties, for and against the project, have flooded the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) with 150,000 pages of comments and documents — 250 pages for every mile of pipeline.

With FERC expected to vote on the project in October, the battle is heading into the home stretch. Hardly a day passes without opponents raising new allegations of harm. Meanwhile, pipeline developers and state government promise the highest levels of environmental review over what has become a high-stakes, fight-to-the-finish drama that both sides are determined to win.

Without an inch of pipeline being laid, the impassioned debate over the ACP already has produced a tangled intersection of concerns: environmental protection, personal property rights, and the role and influence of Dominion Energy, the state’s largest utility and the project’s lead partner.

Supporters, including Richmond-based Dominion, say the ACP would secure an abundant, affordable source of energy that would create jobs and spur economic development. They claim there’s an urgent public need for the project, especially in natural gas-constrained areas such as Hampton Roads.

Dominion has thrown its full force behind the $5 billion pipeline. That should come as no surprise given that the ACP provides the foundation for the company’s long-term strategic growth plan. “We really aren’t making contingency plans for not having the ACP. We believe the ACP will get built,” says Paul Koonce, the CEO of Dominion Generation Group.

The company is counting on the underground pipeline to better serve customers, lower energy costs and provide a reliable backup to a growing portfolio of renewable sources.

Dominion has built its solar portfolio to more than 400 megawatts and continues to make solar acquisitions, while moving ahead with a 12-megawatt offshore wind project off the coast of Virginia Beach.

“If we are to deploy 5,000 megawatts of solar [by 2042] … you can’t do one without the other,” says Koonce. “If we’re going to maintain the dispatchable generation that we have to have to go with the intermittency of solar and other renewables, then we believe that we have to have the ACP.”

Opponents say such arguments ignore the fact that Dominion is part of PJM, a regional grid operator based in Pennsylvania. “There is a ton of base load power in PJM,” says Will Cleveland, a staff attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) in Charlottesville. “We don’t need to generate every megawatt of electricity that’s consumed in Virginia. If you want to protect your customers from price volatility, you participate in the PJM power market.”

Renewable energy advocates question the wisdom of Dominion’s expansion into natural gas at a time when costs for renewables, such as solar and wind energy, are dropping and technologies are breaking new ground in areas such as energy storage. While natural gas produces half the carbon emissions of coal, it’s still a fossil fuel, they say.

“We’re not saying don’t build any natural gas,” says J. R. Tolbert, a Richmond-based vice president of state policy for Advanced Energy Economy, a national nonpartisan, business group that focuses on clean energy. “We’re saying that there are other solutions out there that, if we build thousands of megawatts of natural gas, we’re going to be leaving on the sideline. And those solutions are the options that Fortune 100 and Fortune 500 companies are clamoring for, the same people that we’re trying to get to come and do business in Virginia.”

Environmental impact

Opponents also worry about environmental risk. They say the 42-inch-diameter pipeline would disrupt some of the most pristine areas of Virginia as it passes through 16 miles of national forests, hundreds of rivers and streams and steep mountain terrain. Also along the route are 1,400 Virginia landowners who could see property taken through eminent domain if FERC approves the project.

FERC was scheduled to release a final environmental impact statement on the ACP on July 21, after this story had gone to press.

A draft statement released in December determined that the pipeline “would result in temporary and permanent impacts on the environment and would also result in some adverse effects.” FERC added that such impacts could be reduced to “less-than-significant levels” through mitigating measures taken by pipeline developers and federal regulators.

After the final environmental statement is released, FERC is expected to vote on a permit about 90 days later — if it has a three-person quorum. Since February, the five-member commission has had only two commissioners. President Donald Trump has nominated two candidates for the commission, but they still were awaiting Senate confirmation in mid-July.

Dominion donations

Dominion, a Fortune 500 corporation with annual revenue of $11.4 billion, is a company with deep pockets and political clout. As one of the country’s largest producers and transporters of energy, it has a portfolio of about 26,200 megawatts of generation, 15,000 miles of natural-gas transmission, gathering and storage pipeline, and more than 6 million utility and retail energy customers.

In its Virginia service area, it functions as a utility monopoly, serving 2.5 million customers in this state and eastern North Carolina.

Dominion is regulated by the General Assembly and the State Corporation Commission, and it’s well known that the energy giant is Virginia’s top corporate political donor.

According to the Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), the company gave $442,000 to Democrats and $445,000 to Republicans in Virginia in 2016 and 2017 (through June 1). Dominion officials point out that environmental groups also give hefty donations to politicians. That comparison, says state Sen. J. Chapman Petersen, D-Fairfax County, isn’t exactly apples to apples. “These groups are volunteers, advocates. They don’t get any special protection from state laws.”

Dominion, though, is given “quasi-governmental powers,” notes Petersen. “To give a public-service corporation that amount of power and then allow them to give donations to the people who regulate them, to me, is too much.”

During this year’s General Assembly, Petersen proposed a bill that would have prohibited members of the General Assembly or holders of statewide office from accepting campaign money from public-service corporations like Dominion. The bill failed, but he plans to reintroduce it in 2018.

“Right now people aren’t happy,” he says. “They’re not happy about the pipeline, the coal ash [the disposal of waste from coal-fired power plants] …” and other issues that have dogged Dominion over the past couple years, including legislation passed in 2015 exempting Dominion Virginia Power and Appalachian Power from rate reviews by the State Corporation Commission for seven years.

Petersen tried to repeal the rate freeze this year, but his bill didn’t make it out of committee. He contends that the rationale for the legislation no longer exists since it was predicated on the onerous costs of implementing the Clean Power Plan advocated by then-President Barack Obama. At that time, energy companies, including Dominion, feared the stricter regulations would lead to higher energy costs for customers as companies would be forced to close coal plants. Since then, the CPP has been stayed by the Supreme Court, and President Donald Trump has issued an executive order repealing the policy.

Petersen calls the continued suspension of the rate review, “a gross display of political power and zero benefit for the customer [because it bans customers in Virginia from receiving refunds when electric companies earn excessive profits]. That’s why I did what I did,” he says, during this year’s legislative session.

Dominion has said the rate freeze would help the company stabilize prices for electricity.

The pipeline controversy also has found its way into the gubernatorial race. Northam faces political pressure from anti pipeline groups and Republicans because he has not publicly opposed the pipeline. In a recent radio interview, Northam indicated that if FERC approves the project and mitigating measures could prevent environmental harm, then he would not move to stop it should he be elected governor, a statement Republicans said proves he is for the pipeline. Northam’s campaign disagreed and responded that “Dr. Northam has always said he wants DEQ’s (Department of Environmental Quality) evaluation to be rigorous, based in science, transparent, and to make sure that Virginia takes care of people’s property rights. He believes the facts should dictate the outcome, and his position has not changed.”

Former U. S. Rep. Tom Perriello, Northam’s primary opponent, had made his opposition to the pipeline and refusal to take donations from Dominion key campaign points.

Northam had accepted political donations from Dominion and its executives totaling about $29,500 from January through June, and he also owns stock in the company.

During the same time, Republican gubernatorial nominee Ed Gillespie had received about $13,000 from Dominion. He favors the ACP and the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP), a $3 billion, 300-mile proposed natural gas pipeline that would cross parts of Southwest Virginia.

The MVP has sparked strong opposition as well, but it doesn’t involve a Virginia-based corporate heavyweight.

Dominion and its charitable foundation distribute about $20 million a year in grants within its 18-state footprint, including $8.6 million to Virginia nonprofits in 2016. The company also sponsors numerous events and is building a new corporate headquarters in downtown Richmond.

It’s headed by CEO Thomas F. Farrell II, one of Virginia’s most powerful business executives. Farrell serves on several of the state’s high-profile boards. He is a member on the board of trustees of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and is chairman of the Richmond Performing Arts Center and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Farrell is a former rector of the University of Virginia board of visitors and the former chairman of the Governor’s Commission on Higher Education. He also was among state business leaders who pushed for the creation of GO Virginia, a new regional economic development initiative, where he serves as a board member.

The political pushback against Dominion comes at a time of growing political populism. During the June primary, 61 Democratic challengers for House of Delegates seats said they would not take donations from the company. “What we have emerging is a branch of the Democratic Party, a progressive wing, that is skeptical of the business-friendly orientation that has dominated Virginia politics for a century and a half,” says Quentin Kidd, a political analyst and the director of the Wason Center at Christopher Newport University in Newport News.

While Virginia has seen populist politicians before, today’s climate “is a Bernie Sanders, business-skeptical populism,” adds Kidd, “and that’s the difference.”

The shale revolution

Politics aside, “All infrastructure is controversial,” says Cathy Landry, a spokeswoman for Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, a trade association that represents the operators of interstate natural gas pipelines.

In the last decade the country has seen a boom in natural-gas development, thanks to the Marcellus and Utica shale formations in Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio. Advances in hydraulic fracturing, a horizontal drilling process challenged by some environmentalists, provide access to these rich gas reserves. And with the shale close to high-demand markets in the Northeast, “this certainly has been a game changer,” says Landry. With shale deposits expected to last 100 years, advocates hail a new era of energy security for America.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported last year that natural gas provided 34 percent of the total electricity generation in the country, surpassing coal to become the leading generation source.

The case for the ACP

With a 48 percent interest, Dominion is the lead partner in the ACP along with Duke Energy, 47 percent; and Southern Co. Gas, 5 percent. The partners extol the economic development gains they say would come from the pipeline: a total of 17,240 jobs during construction, $2.7 billion in overall economic impact and an average of $4.2 million annually in tax revenues to local governments along the three-state route.

Matt Yonka, president of the Virginia State Building and Construction Trades, an organization that represents union construction trades throughout the state, says about 8,800 of those jobs would be in Virginia. The construction would require welders, electricians, pipefitters and industrial equipment operators. “They will bring in their supervision,” he says of the pipeline developers, “and then they will hire local Virginians who work through us.”

Once the pipeline begins operation, one survey claims, it would support about 1,300 permanent jobs in Virginia, including positions that could materialize from increased manufacturing, a number opponents dispute.

While Dominion would operate it, subsidiaries of the partners and others would use the ACP, with 92 percent of the capacity subscribed, says Leopold. “We knew there was going to be some opposition,” she says. “Our focus is on getting it done to meet the urgent public need, to protect public safety and to do it environmentally responsibly.”

Leopold says the origins for the ACP came in 2014 when Duke Energy and Piedmont Natural Gas requested proposals for a pipeline because of natural gas constraints in the state. In eastern North Carolina and eastern Virginia, “there are constraints today in being able to heat the homes, let alone building new homes or businesses in the area,” says Leopold. “So that’s the first piece of public need.”

A second driver was stricter federal regulations on power plant emissions of mercury and other toxic metals. Although shot down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015, the new rules prompted energy companies to update or close coal-fired plants. The Clean Power Plan under Obama’s administration also called for reduced carbon emissions. While that plan appears to be dead, Dominion officials anticipate future national and state energy policy to include limitations on greenhouse gas emissions. In Virginia, Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe has directed the state to come up with regulations reducing carbon emissions from power plants by December.

The upshot of the movement to lower carbon emissions: the building of more natural gas-fired plants. In the past four years, Dominion Energy has closed several coal-fired units and brought more than 3,000 megawatts of gas production on line. It already has opened three natural gas-fired plants in Virginia and will add another 1,500 megawatts of natural gas when the Greensville Power Plant is completed in December 2018.

For Jim Kibler, president of Virginia Natural Gas in Norfolk (a subsidiary of Southern Co. Gas), the pipeline can’t come fast enough. His utility serves 300,000 homes and businesses in Hampton Roads, and he says it doesn’t have excess capacity.

During a polar vortex winter storm in 2014, Kibler says, the company shut off the region’s 100 largest industrial customers. “We had to shut them off for days so we could keep the heat on for schools, hospitals, nursing homes and residents.”

While that was an extreme storm, Kibler says the region needs an investment in new infrastructure. “When the state brings us a prospect to locate here, we have not been able to compete with other regions where the pipeline system is less constrained. Whatever capacity we’ve been able to offer is on an interruptible basis. This customer signs up for service knowing that if we experience extreme weather, we have the right to interrupt their power.”

Another area of concern is the ability to convert large industrial customers to natural gas. The Newport News Shipbuilding division of Huntington Ingalls recently converted its steam-generation power plant from fuel oil to natural gas. Tom Cosgrove, the shipyard’s community relations manager, says the savings have been tremendous. In 2016, the first year the shipyard fully transitioned to natural gas, costs for fuel, labor and maintenance came to $4 million, an 80 percent drop from the $20 million spent in 2013, the last year the shipyard relied solely on oil.

“As more companies are looking to make that change, the infrastructure needs to be there to support it,” says Cosgrove.

The case against the ACP

Personal property rights, public need and Virginia’s plans to protect water quality have emerged as key points of opposition.

Today, Palmer’s daughter lives on the land in a log home at the top of a hill overlooking a scenic mountain ridge. According to Palmer, the ACP’s route runs about 1,000 feet from the rear of her daughter’s home, close to the ridge. “It just makes me ill that they’re going to come through with a pipeline,” she says.

Palmer and other private landowners filed suit against the ACP after their property was surveyed for the pipeline without their permission, which is legal under a controversial law in Virginia that was recently upheld by the state’s Supreme Court. After she initially refused permission, Palmer said Dominion sued her, and she countersued. Palmer’s case contended that natural gas companies should not be allowed to survey private property without the landowner’s consent.

A circuit court judge ruled against Palmer in Staunton, and she appealed the ruling to the Virginia Supreme Court. In July, the court upheld the constitutionality of Virginia’s survey law, which requires companies to notify landowners about plans and dates for surveying their lands.

According to Palmer, pipeline crews would clear about a 125-foot-wide construction corridor across 110 acres of her land, with a 50-foot easement taken for the pipeline’s permanent right of way. With a gas pipeline on her property, she’s afraid she won’t be able to sell the land in the future. “If there’s a leak, I worry about what that would do.”

Public need

“There is no doubt that we can keep the lights on in Virginia without the pipeline,” says the SELC’s Cleveland. On behalf of a coalition of eight environmental groups, SELC filed a motion in June with FERC seeking an evidentiary hearing on the public need for the pipeline. Such hearings include testimony and cross-examination, which could delay FERC’s decision.

With increased energy efficiency and the availability of solar and wind alternatives, the coalition claims that justification for the project has eroded in the three years since it was proposed in September 2014.

The motion also challenges agreements that Dominion and Duke Energy have with subsidiaries. In essence the companies are contracting with themselves, says Greg Buppert, the SELC senior attorney who filed the motion. “That’s not an arm’s length transaction that actually reflects what’s going on in the market.”

“In other words,” the motion says, “these companies are gambling with ratepayer money in order to build their $5 to $6 billion project on which pipeline developers will receive a lucrative 14-15 percent rate of return.”

Leopold says that the ACP has negotiated a rate of return with FERC on the project, but she’s not revealing what the rate is. She did say that a blanket statement saying all pipelines are guaranteed a certain rate, such as 14 percent, is incorrect. “Until the construction is done, we won’t even know what it is. So it’s not fixed that way.”

In its most recent long-term strategic plan filed with the SCC, Dominion says that it expects wholesale and retail customer energy sales to grow at annual rates of 1.2 percent and 1.3 percent respectively, over the 25-year planning period.

Based on an earlier study it commissioned, SELC says demand forecasts will be level or declining through 2030 and that existing pipelines can supply enough fuel. PJM’s peak demand forecast for Dominion for 2017 is 1,251 megawatts less than in 2016. Dominion says that revisions to PJM’s load forecasting model and the lack of market specifics such as Virginia’s new data center growth, account for the lower number.

Water quality

One of the most intense skirmishes focuses on water quality. In late June, the state Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) announced that it was expanding its review of both the ACP and the MVP pipelines in areas not covered by a blanket permit used by the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers. The corps’ purview assesses work on utility projects that cross streams and wetlands.

So in addition to what is known as the Corps’ Nationwide Permit 12, Virginia will require additional conditions for erosion and sediment control. DEQ’s action came after Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition and other groups opposed to the ACP filed suit against the agency.

The coalition challenged DEQ’s decision to allow the Corps’ blanket permit to be the authority for protecting the state’s water quality in areas near stream and wetlands crossings. “Areas in and around these streams are some of the most damaging, risky places to be digging, boring and blasting, which they will be doing,” says David Sligh, a spokesman for the coalition and a former DEQ senior engineer.

He is not appeased by the schedule of public hearings in August to give citizens a chance to comment on DEQ’s proposed water quality certification of each pipeline project under Section 401 of the Clean Water Act. DEQ’s announcement “essentially portends that the state is somehow doing more than they are required to do. That’s simply not true,” says Sligh. “They are still proposing to do far less than is necessary for our water quality, and they’re choosing to continue to rely on the Corps of Engineers blanket permit, which is completely inadequate.”

Pressure from environmental groups on water quality is not surprising. New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation recently refused to grant a water permit for the 125-mile Constitution Pipeline, effectively halting the project. The $925 million pipeline had received approval from FERC and permits from the state of Pennsylvania. The pipeline’s developer is fighting the state’s action in an appeals court.

Governor’s assurances

Gov. McAuliffe, who supports the ACP, is comfortable with DEQ’s plan. He tells Virginia Business that DEQ will require ACP and MVP pipeline developers to submit detailed erosion and sediment control plans “for every foot of land disturbance, and these plans must protect water quality during and after construction. The plans will be posted for public review, and DEQ will hire inspectors to oversee the construction process to ensure compliance.”

A final decision on certification will be made at a public meeting of the State Water Control Board.

Despite the intense debate and threats of more litigation should the pipeline be approved, the governor is not backing away from his support. “Many businesses need access to natural gas to support manufacturing processes. Hampton Roads is a natural gas-constrained region that has seen some economic development activities stunted because of this constraint. If we are going to grow our economy, we need to continue to build and expand our energy infrastructure.”

-