Genetic mapping

Shenandoah partnership will be first phase of Inova Center for Personalized Health

Genetic mapping

Shenandoah partnership will be first phase of Inova Center for Personalized Health

Vienna resident Alyssa Lehman’s youngest child is less than a year old. Nonetheless, Lehman already is armed with the confidence that her daughter would respond well to more than 20 medications.

Her daughter was born in July at Inova Fairfax Hospital, the flagship facility of Inova Health System, which likely is the first in the country to offer MediMap testing for newborns. With a simple cheek swab, Inova uses a baby’s genetics to document how that child could react to more than 20 drugs. That list includes codeine, a common pain relief drug used for children. Some children metabolize the drug too quickly, which in extreme cases can cause death.

The other drugs on the test, which range from blood thinners to antidepressants, are chosen because they have genetic markers determining how a patient will react to them. “I think it’s great to have a report that is so specific to my child,” says Lehman, a mother of three. “Usually doctors are doing a guessing game about correct dosages and whether a medication will work.”

The MediMap program is popular. More than 70 percent of mothers are electing to have their newborn babies tested, and there is no extra cost for the patient. The tests have been so successful that they are being added to obstetrics departments at other Inova hospitals.

“These kids won’t need these medicines for some time,” says Dr. John Deeken, chief operating officer of the Inova Translational Medicine Institute, a research institute charged with applying genomic and clinical research to personalized health care. “So is it necessary to do it today? No. But your genes don’t change. We think this starts the child on the right path to personalized health.”

Inova makes genetic specialists available for parents and advises them to share the test information with their pediatricians. But the science behind the test, pharmacogenomics, or PGx, is complex and barely taught at most medical schools. There also is a shortage of doctors and nurses who can interpret PGx data.

Inova wants to revolutionize health care through personalized medicine at its new Inova Center for Personalized Health (ICPH) campus in Fairfax County, but to do that, it needs more professionals well versed in the field of pharmacogenomics.

Last month, Inova and Shenandoah University announced a partnership to launch graduate-level programs in personalized medicine and other high-need fields. “I think we can hire every single person that graduates and comes through these programs,” says Todd Stottlemyer, CEO of the ICPH. “There’s a real shortage of outstanding health professionals [in the field]. The partnership allows us to capitalize on the strengths of the university to make sure we have the pipeline of outstanding talent in some areas that are relatively new.”

First occupants on campus

Notably, Shenandoah’s students and professors will be the first occupants on the ICPH campus, a symbol of the health system’s ambition to become a global destination for research and clinical care centered on personalized medicine. Inova recently bought the 117-acre property, located directly across the street from Inova Fairfax, from the Irving, Texas-based energy company Exxon Mobil. Most of the programs will begin in August.

The Shenandoah programs will occupy 28,000 square feet of classroom and laboratory space in the education wing of the former Exxon Mobil offices, which currently are under renovation. Inova will invest $5 million to create the programs.

ICPH also has signed partnerships with George Mason University and the University of Virginia. Those programs will focus on research, while Shenandoah’s programs will focus on teaching clinically trained professionals.

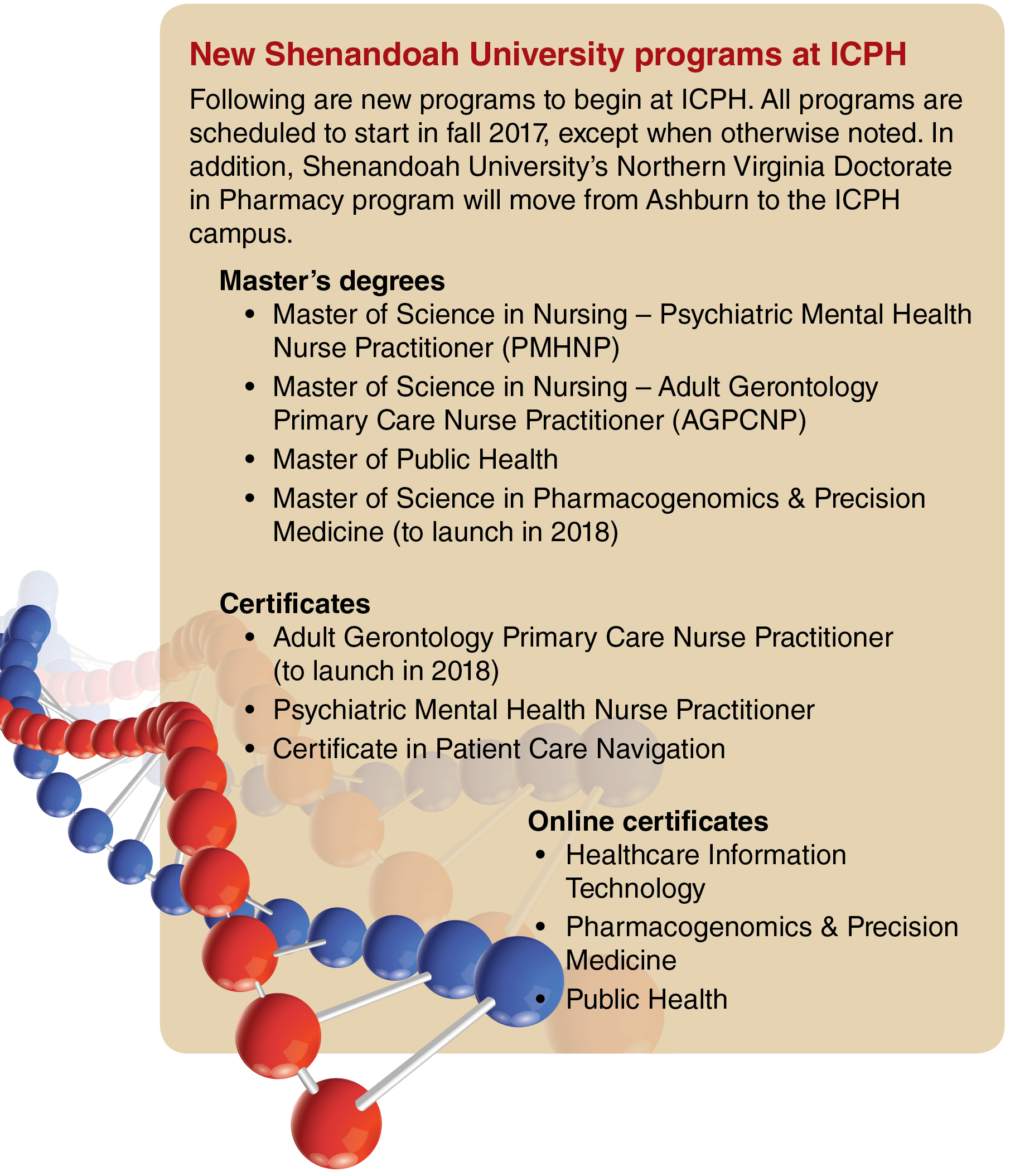

The new programs include master’s degree and postgraduate certificate programs, which are expected to have about 250 students. In addition to the new programs, Shenandoah will move the Northern Virginia campus of its Bernard J. Dunn School of Pharmacy, now in Ashburn, to ICPH.

Many students will be able to do clinical rotations at Inova facilities, including Inova Fairfax. Not only will that opportunity provide hands-on training for students, but Inova also will be able to hire practitioners already trained in its policies and procedures and applicable medicine.

“Inova has identified two things here,” says Fitzsimmons. “They’ve identified where the societal needs are emerging because of the aging population, and the second piece is that we need practitioners with new sets of skills. We just don’t have enough psychiatric nurses, genetic nurses or professionals focusing on public health.”

The new programs include both master’s degrees and postgraduate degrees in:

- public health,

- pharmacogenomics and precision medicine,

- and, for nurse practitioners, psychiatric mental health and gerontology primary care.

- Certificates in health-care information technology and patient care navigation also will be offered. The certificates in health-care IT, public health, and pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine will be offered online.

Working relationship

The Inova-Shenandoah partnership is a natural one, the institutions say. They have been working together on programs such as nursing, physical therapy and physician-assistant studies for two decades.

In addition, Shenandoah was one of the first pharmacy schools in the country to incorporate pharmacogenomics into its core curriculum, and its professors are active in PGx research, says Arthur Harralson, the associate dean for research and a professor of pharmacogenomics at the pharmacy school.

For example, the FDA adopted Shenandoah researchers’ method of assigning genotypes to Warfarin, a blood thinner used to prevent clots, strokes and heart attacks. The pharmacy school also is part of a federally funded program studying pharmacogenomics in African-American patients.

PGx is an integral part of Shenandoah’s curriculum, with students required to take four classes on the subject.

That puts Shenandoah ahead of the curve. In 2016, new national pharmacy school standards were adopted saying that PGx should be included in curricula. “We had it woven into our program long before that,” says Robert DiCenzo, who is dean of Shenandoah’s School of Pharmacy. “There are now requirements to have pharmacogenomics within pharmacy education, but many of the programs are just starting to look for ways to put that in.”

Pharmacogenomics has the potential to be a game-changer in medicine. About 10 percent of drugs have known markers that can affect a patient’s reaction to medicine, influencing its efficacy or toxicity, says Deeken with Inova.

PGx also can be used to determine the correct dosage for a patient. “I think it’s probably one of the most exciting areas of medicine today: the intersection of pharmacology and genomics and the ability to tell a healthy individual that they shouldn’t take a drug,” says Stottlemyer.

In addition to its MediMap test for infants, Inova is incorporating genetic tests for patients being treated for high cholesterol, coronary disease and psychiatric conditions, such as adolescents being treated for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Little exposure in med school

But while doctors in some areas of medicine, such as cardiology and oncology, are well versed in PGx, most primary-care doctors and pediatricians are not.

Harralson of Shenandoah University says a recent study showed that the average medical school student gets only four hours of lecture on pharmacogenomics.

That lack of education is holding the field back.

“Physician education and physician adoption [probably are two of] the reasons that the field continues to progress, but not rapidly progress,” Deeken says.

That’s where Inova and Shenandoah hope their new certificate programs will help. They will include specialized modules for practitioners in different fields. “The rate of change is exponential,” says Fitzsimmons. “That’s why it’s important not just to be training new practitioners, but as they go out into the field, to bring them back every five or 10 years.”

Stottlemyer says pharmacogenomics is revolutionizing the health-care field, giving doctors ways to prevent disease and help their patients stay healthy. “This is fundamentally about changing the human condition,” says Stottlemyer. “You have an industry that’s going through a significant disruption. Disrupting from the inside out is ambitious and not easy to do, and you’ve got to have partners that are agile, quick and entrepreneurial like Shenandoah University to help you do that.”

t