Hollins University blends liberal arts and job preparation

Tim Thornton //February 2, 2017//

Hollins University blends liberal arts and job preparation

Tim Thornton// February 2, 2017//

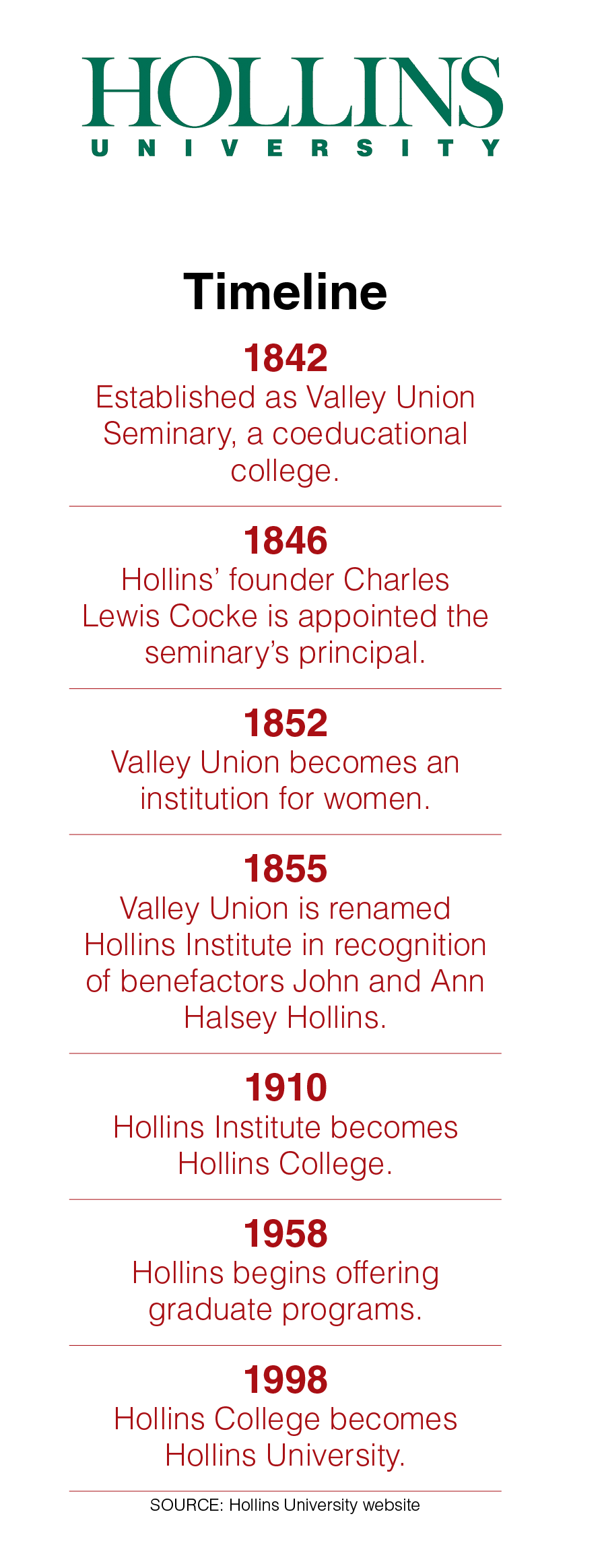

Hollins University turns 175 this year.

“There aren’t many colleges in the country who can claim that kind of history,” says Hollins President Nancy Gray. “We have several of them in Virginia, but it’s unusual by national standards.”

“There aren’t many colleges in the country who can claim that kind of history,” says Hollins President Nancy Gray. “We have several of them in Virginia, but it’s unusual by national standards.”

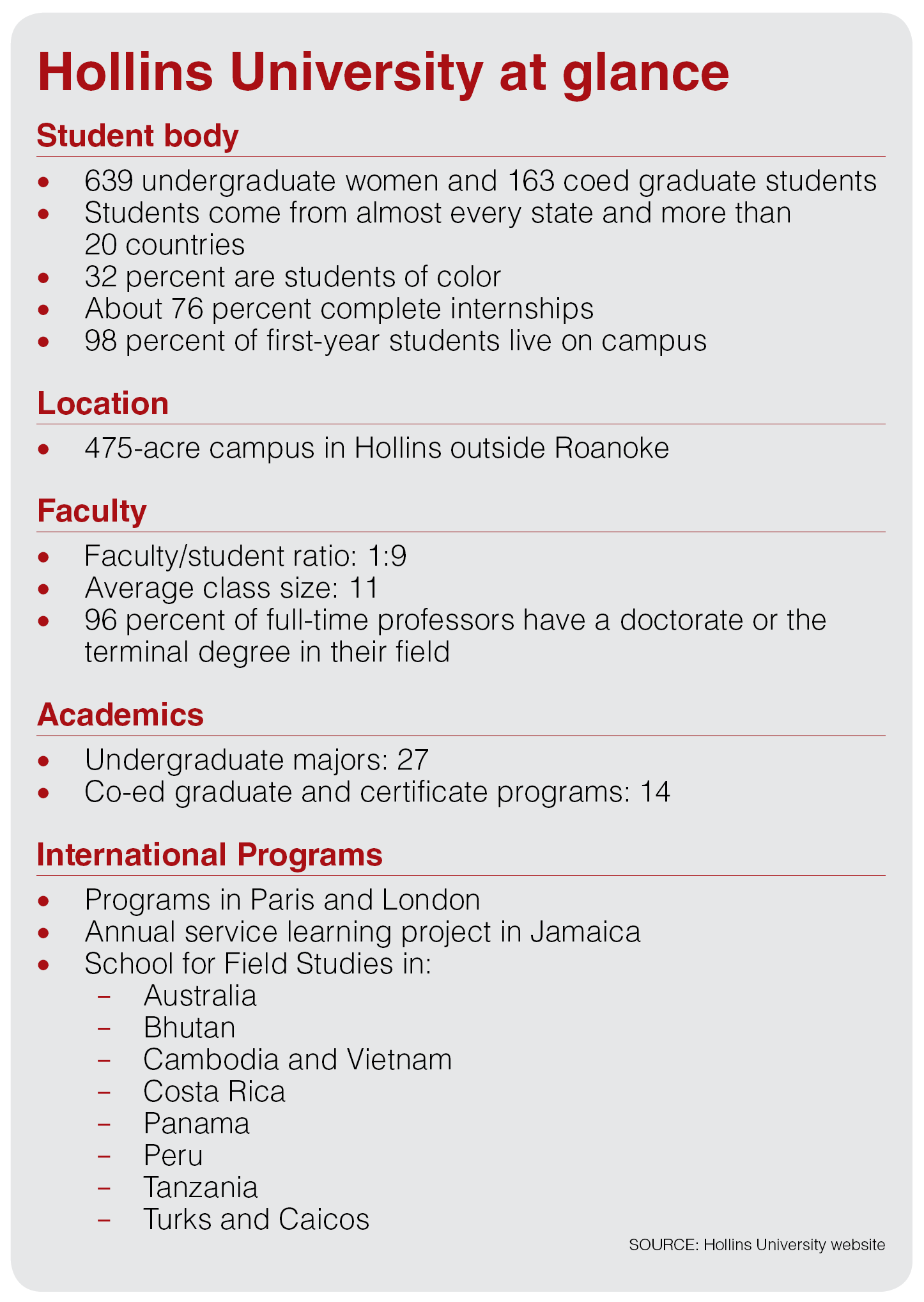

The women’s college just outside of Roanoke approaches the milestone with no debt, a dozen-year string of balanced budgets, a large and growing endowment, and an apparently healthy relationship with young women seeking an education. The 234-member freshman class that joined the Hollins sisterhood last fall was the university’s largest in 17 years.

The next freshman class will be greeted by a new president. Gray, who will have been Hollins’ president for 12½ years when this semester ends, says this is “a natural stopping point” and “a great time to hand Hollins off in a strong position to my successor, Pareena Lawrence.”

Hollins’ board of trustees conducted a three-month search and in November chose Lawrence to be the university’s 12th president. She is provost and chief academic officer at Augustana College, a 156-year-old, 2,500-student liberal arts school in Rock Island, Ill. In a letter to the Hollins community announcing Lawrence’s selection, search committee member Alex Trower says, “Pareena embodies all that is a Hollins woman: smart, articulate, warm, energetic, caring, engaged and completely aligned with our mission.”

Judy Lambeth, who chairs the board of trustees and led the search committee, says, “We were looking for someone who is clearly committed to women’s education. That is what Hollins is all about. That is our mission. We still believe in that wholeheartedly.”

‘Prepared for anything’

Offering a liberal arts education to an all-female student body in small classes may seem out of step in this era of coeducation and high-tech training at ever-larger universities. But out of step doesn’t mean out of date.

“We believe so strongly in that core mission of liberal arts education and education for women,” Gray says. “But we also believe that an institution, in order to thrive, has to be in the world as it is today, because we function in a world that is constantly changing … And so, several years ago now, we recognized the need to diversify our student body and have done that successfully from a host of perspectives — racial, ethnic, socio-economic.”

Part of being in the world as it is today, Gray says, is preparing for the world as it will be.

“I mean, the reality is, technology is changing so fast, we can’t possibly prepare students with technical skills for the job market that are going to persist because they’re going to be out of date by the time they graduate or a few years later,” she says.

“However, if we can prepare them to think, to solve problems, prepare them with quantitative skills, prepare them to communicate effectively orally and in writing, prepare them to work effectively in teams, they’re going to be prepared for anything that happens in the job market, no matter how it changes … And employers are telling us that,” she says. “The liberal arts are maybe more relevant today than they’ve ever been, not less.”

That can be a hard sell for parents looking at a sticker price in the current academic year of more than $49,000 in tuition, fees, room and board at a school where English and studio art are among the most popular majors. “We try to connect the dots for them,” Gray says.

Alumnae network

Alumnae network

No matter what a Hollins’ woman majors in, she has a chance to study abroad, participate in the university’s Batten Leadership Institute Program and become involved in undergraduate research. For parents worried about their daughters’ employability, the most encouraging aspect of a

Hollins education may be the network of its graduates willing to share their knowledge and experience with students.

Lisa Birnbach, author of “The Preppy Handbook,” recognized the importance of the Hollins’ alumnae network in a Vanity Fair article about women’s colleges thriving “in this era of post-feminism, gender fluidity and skyrocketing tuitions.” Of Hollins, Birnbach wrote, “The secret sauce is the intensely involved alumnae, who return to campus whenever they’re invited as mentors, and who provide internship opportunities to the students.”

During the most recent January term, Gray says, Hollins had 30 or more students in New York City; 30 or more in Washington, D.C.; about 50 in Roanoke and others scattered in other cities — all working with and learning from Hollins alumnae. The alumnae also offered programs on résumé writing, interviewing and other skills valuable for anyone looking for her first job after college.

“They’re sharing their experience with students and giving them feedback,” Gray says. “Our hope is these internships will turn into jobs.”

In addition to offering internships, alumnae return to campus every fall for the university’s Career Connections Conference. Classes are canceled so students can attend alumnae-led workshops ranging from what it takes to own and run a business to how to find an apartment in a strange city. When they’re not on campus or hosting students’ internships, many alumnae serve as career mentors and connect with students through Skype sessions.

Though some of these programs and emphases are relatively new, Hollins graduates have been finding success for some time. The first woman assigned to cover the White House for a television network, the founder of Emily’s List, the youngest woman to win the Man Booker Prize and the author of “Goodnight Moon” were all Hollins women. The university has produced four Pulitzer Prize winners and one U.S. poet laureate. Yet, perhaps because it has only 639 undergraduates, Hollins has remained, according to Birnbach’s Vanity Fair article, “a cozy place where everything is for the delectation of the undergraduate women who attend it.”

Lambeth, the board of trustees chair, agrees. “It’s tailored to you,” she says. “You come in, and you’re able to make that education fit your priorities. It’s just a unique place.

“I came in like a tangled-up puppet, like so many teenagers are,” she adds. “It didn’t take long before I realized that Hollins is helping me have these capabilities, maybe I should put them to use.”

Fewer single-sex schools

Perhaps the most surprising thing about a Hollins education is that it’s still available.

In 1857, Hollins founder Charles Cocke declared his school recognized “the principle that in the present state of society in our country young women require the same thorough and rigid training as that afforded to young men.” That was a fairly radical idea for its time.

During the next century or so, a growing number of people accepted Cocke’s position. Some of them even thought women should be allowed to get that education at the same schools as men.

As more colleges and universities became co-ed, single-sex schools became scarce. In 1970, Virginia was home to 11 women’s colleges. Now it has three. Sweet Briar College nearly closed in 2015, before being rescued from financial problems by a determined group of alumnae. Mary Baldwin University, also celebrating its 175th anniversary this year, plans to admit men to a residential program for the first time this fall, though it will be separate from the women’s college.

Raising money, retiring debt

Raising money, retiring debt

Hollins has had its own financial troubles and confronted the specter of admitting men, but it has come to a very different place than either of its Virginia sisters.

In 2000, when debt was high, the endowment was shrinking and the campus needed repairs, Hollins solicited ideas from the university community and suggested that every possible solution would be weighed. Most of that community thought any solution but coeducation should be considered.

Gray became Hollins president in January 2005, stepping into an ongoing fundraising campaign aimed at retiring its debt and increasing the endowment. The publicly announced goal was $125 million. The campaign raised $161 million by 2010. The endowment had grown to $171 million by 2015.

Gray credits alumnae, faculty, trustees and “extraordinarily visionary donors,” people willing to give substantial amounts of money without getting a program or a building named after them in exchange.

Since retiring its debt in 2007, the university has been committed to staying out of debt, paying for renovations and other capital projects through fundraising rather than loans.

More than half the buildings on campus — including the theater, the student center, the humanities building, the dance studio and historic houses — have been renovated or updated since Gray took office. The university has added the Richard Wetherill Visual Arts Center and Eleanor D. Wilson Museum, drilled geothermal wells and is renovating the science building.

Being debt free relieves pressure, Gray says, but she and her leadership team agreed early on that a large endowment was critical.

“Those large endowments allow you to provide a measure of academic excellence for your students that exceeds what they can pay in tuition and fees,” Gray says. An ample endowment also allows “the institution to respond to great opportunities as they arise and to get through tough patches as they arise — both of which are inevitable in the life of any institution.”

To celebrate the university’s 175th anniversary, Hollins is appealing to key donors with a quiet fundraising campaign that had raised $44.5 million by August. In November, Elizabeth Hall McDonnell and her husband, James S. McDonnell III, pledged $20 million to Hollins’ endowment. It’s the largest gift in the university’s history. Gray says Hollins has received two $1 million commitments since then, and another donor has offered $5 million if the university can raise another $10 million before Gray leaves campus on June 30.

Graduate programs

Hollins has leveraged its academic strengths to create more income, too. “We believe strongly that our core mission is undergraduate liberal-arts education for women,” Gray says. “We also, though, have built out now an array of 10 co-ed graduate programs that build on our undergraduate strengths.”

Hollins’ first graduate program, in creative writing, was created in 1960 and may be the college’s biggest claim to fame. Most of the programs added since are related to writing — including playwriting, screenwriting and children’s literature. Hollins also offers graduate degrees in teaching, dance and liberal studies. Some offer summer residences on campus.

“In the summer, we become a residential co-ed graduate campus,” Gray says. That allows Hollins to get more use out of its on-campus facilities and to bring in visiting faculty. “That’s been an important part of our income, in addition to the undergraduate tuition and fees,” Gray says.

What’s made the programs work financially, Lambeth says, is they work academically. Instead of adding executive MBA or nursing programs, Hollins went with its strengths.

“We’re small, and I’m not sure we have the luxury of a big innovation funnel — of looking at, ‘Hey, here’s what’s making money in the market. Let’s go do it,’” Lambeth says. “In a weird way, sometimes having to act within your resources makes you really pay attention to what you’re doing. You can squander a lot of money if you have a lot of money.”

Lambeth sounds confident about Hollins’ future, although she acknowledges there will be challenges.

“I think running a university is an incredibly complex task,” Lambeth says. “People in the world underestimate the incredible complexity of an academic institution. I’ve been in Fortune 500 companies, and I can tell you a university is every bit as complex as that universe is.”

Gray has proved she can handle that complex job, Lambeth says, adding she believes the incoming president has that ability, too. “We’ve selected a leader capable of running a complex system at a complex time,” Lambeth says.

-