GMU research addresses world issues

M.J. McAteer //August 30, 2016//

Forget about those clichéd images of professors closeted in ivory towers, working away on obscure subjects with no practical purpose. Research at George Mason University is aimed at producing results that have real-life repercussions.

In the past 20 years, research has become the university’s growth industry. In fiscal year 2007, it spent $67.6 million on research. By 2015, that figure had increased by 49 percent to $101 million. The school now ranks among the top 20 public universities in the country for its research in the social and economic sciences and among the top 50 for math and computer science. It further has been elevated to the tier of “highest research activity” by the prestigious Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education.

Terry L. Clower, director of the GMU’s Center for Regional Analysis, says that “very much like a business, we are creating jobs, not just through our spending, but because of how business and government benefit from the research we do.” Economic data supplied by the center help public and private entities in the region make more informed decisions.

Work at Mason covers the social, biological and physical sciences, with concentrations that include sustainability and the environment; regional, national and international policy; technology and information; and homeland and global security. The school has almost 100 research centers devoted to fields ranging from computational fluid dynamics to women and gender.

That’s a lot of irons in the fire, and Crawford says that the university intends to concentrate on expanding in “three multidisciplinary areas that align with the economy of the area.”

Biotech and health

The first, and, arguably, most important, is biotech and health. Northern Virginia is seeking to position itself as a locus for personalized medicine, and George Mason is joining with Inova Health System at the forefront of that ambition.

On the former ExxonMobil campus in Fairfax, Inova is opening a huge complex that will be largely devoted to translational medicine, which uses knowledge from research to develop new treatments and drugs. There and elsewhere, the health-care system will collaborate with Mason on innovative treatments, particularly for cancer and heart and metabolic diseases. In addition, Inova and the university will form the Institute for Biomedical Innovation, which Crawford describes as “an intellectual community” that will facilitate the interaction of scientists and clinicians.

The university already is doing intensive work in the fields of genomics and bioinformatics, with many of its labs located on or adjacent to Mason’s recently designated science campus in Prince William County.

At its Center for Applied Proteomics and Molecular Medicine in Prince William, for instance, scientists are identifying biomarkers in body fluids that might predict disease. Co-director Lance A. Liotta says that a pilot breast-cancer program, currently in its third round of testing, is showing positive results.

Of particular interest in a state in which Lyme disease is endemic, his team also has developed a more accurate test for the tick-borne disease. “Thousands of patients under conventional testing get a wrong diagnosis 50 percent of the time,” Liotta says. The accuracy of the center’s new test is more than 90 percent.

At Mason’s MicroBiome Analysis Center, the role of the microbial environment in the human gut, mouth, and urogenital and respiratory tracts is being examined.

“We’re so clean that the body doesn’t get exposed to the proper antigens anymore,” says Director Patrick Gillevet. He noted that an imbalance or maladaptation of microbes in the body is suspected of having links to conditions as different as inflammatory bowel disease, cirrhosis of the liver and autism.

In the near term, the center is working on replacing the invasive colonoscopy procedure currently in use with a test that would reveal the presence of polyps through a test of stool samples.

The Center for Neural Informatics, Neural Structures, and Neural Plasticity, part of the Krasnow Institute for Advanced Study, puts the human brain under the microscope.

“We are at the very beginning,” says Giorgio Ascoli, the center’s founding director. “We don’t know the code yet for neurons.”

To remedy that, Ascoli’s scientists have been compiling a database of neurons, 50,000 so far. The long-term application of the center’s efforts would be to understand the effects of aging on the brain and to build artificial brains or computers that more closely mimic humans.

The quest at the National Center for Biodefense and Infectious Diseases is no less sweeping. The animal research facility seeks to come up with strategies for fighting airborne bioterrorist attacks. Additionally, it contracts with commercial companies to evaluate antiviral drugs.

Executive Director Charles Bailey says the center’s latest target is the Zika virus. At the invitation of the Costa Rican ambassador to the United States, Bailey’s scientists are traveling to Central America to engage in a joint investigation of this burgeoning threat to human health.

The center’s influence at home, too, is significant. “We are serving as a magnet for biotech industry in Northern Virginia,” Bailey says.

Security and resilience

The second prong of future research at Mason will be what Crawford calls security and resilience, which includes engineering, cybersecurity and the social sciences. As with the biotech and health care, the intention is to do “research of consequence,” she says, with outcomes that address existing needs.

Faculty members at Mason’s Volgenau School of Engineering hold 80 patents, and at the school’s six centers and six labs, dozens of studies are being conducted on topics ranging from air transportation to secure information systems.

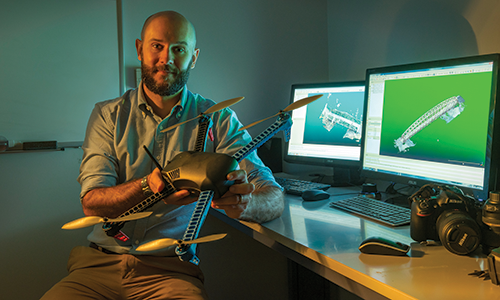

“We don’t get great data right now,” Lattanzi says. With his drone, however, the assistant professor of structural engineering can capture a previously unmatched level of detail, down to the micro-millimeter level. The images then can be assembled into a 3-D virtual reality model of the structure.

Lattanzi took his drone to Haiti after the devastating earthquake there in 2010. “A major part of our research is the post-disaster assessment,” he says. He is gratified that his drone has attracted significant interest from local communities and private businesses. Getting it “into the hands of practitioners,” is his ultimate goal, he says.

Information, communication and entertainment

Mason’s third research priority will be information, communication and entertainment. Because so much of the work underway at the school is interdisciplinary, many projects could fit into more than one of Crawford’s categories. This third area is broad enough to encompass studies as diverse as the effects of digital media on African-American families to the reaction of a population to a nuclear attack.

Mason’s Center for Geospatial Intelligence deals with information and communication. Its analysts examine how data is amassed and disseminated about everything from physical features and man-made structures to people and events.

Information used to flow from the top down, says Director Anthony Stefanidis, but no more. Technology has forever changed that age-old paradigm. Information today is, instead, generated and gathered through multiple outlets, including crowdsourcing, social media, digital images and sensor networks. One of the center’s recent projects looked at how activity on Twitter provided information about an earthquake. In that study of the 2011 earthquake on the East Coast, tweets, the study found, functioned as a human sensor network.

Because the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency is in Springfield, “NoVa is the epicenter of geospatial intelligence,” Stefanidis says, and his center has positioned itself to be a crucial part of that.

At the university’s Institute for Immigration Research, the goal is to provide accurate data about immigrants, despite a highly politicized environment.

Executive Director Monica Gomez Isaac says her institute is creating a data base using statistics from the American Community Survey, which is conducted annually. Through the survey, the institute is able to create maps of immigrant populations in specific communities. If, say, a Fairfax official wants to know the median income of immigrants in the county or the level of their educational attainment, that information can be found on the center’s Data on Demand.

In June, the institute co-authored a report that showed the prominent role that immigrants play in health care. Although immigrants make up just 13 percent of the U.S. population, the institute found that they represent 40 percent of all medical scientists and 28 percent of physicians and surgeons.

Gomez’s organization, like so many others at Mason, sees itself playing a dual role. Its work not only is aimed at bolstering the NoVa economy, but, is as appropriate for a nonprofit institution, at advancing the public good.

“We are pushing to translate our research outcomes, not necessarily commercialize them,” Crawford says. “At Mason, we want to be globally renowned and regionally relevant.”