A big league move?

Business groups believe a Richmond-Hampton Roads mega-region will be a major competitor

A big league move?

Business groups believe a Richmond-Hampton Roads mega-region will be a major competitor

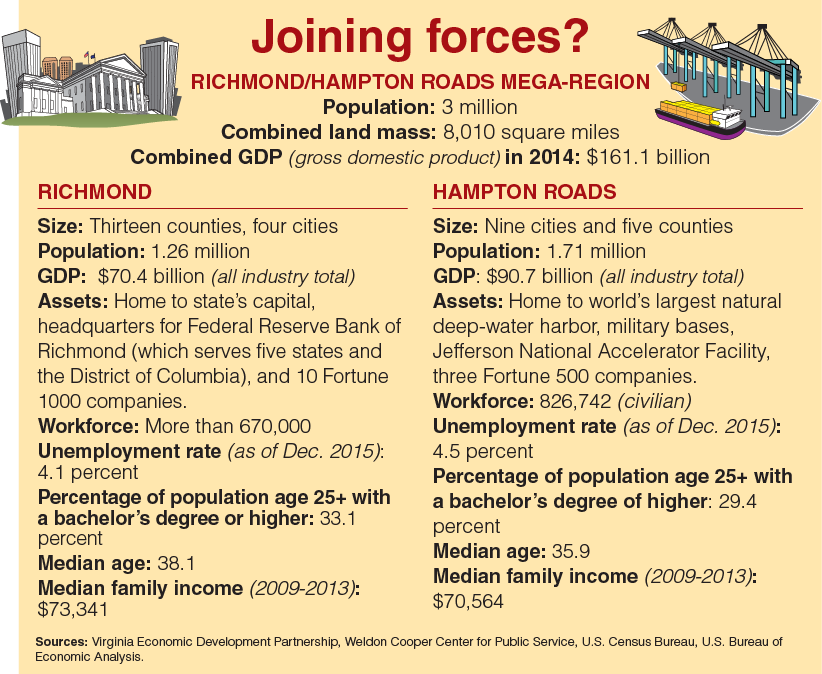

When Tom Frantz envisions the future, he doesn’t see Richmond and Hampton Roads as separate places. He sees a “mega-region” of 3 million people, stretching from the sands of Virginia Beach to the stately columns of Richmond’s state Capitol.

The chairman emeritus of the Williams Mullen law firm and a leader in economic development initiatives, Frantz foresees collaborative alliances in biosciences and advanced manufacturing. They would be supported by transportation systems linking the two metros. People and goods could travel back and forth via a widened Interstate 64, an improved U.S. 460, a high-speed train or a barge on the James River.

The chairman emeritus of the Williams Mullen law firm and a leader in economic development initiatives, Frantz foresees collaborative alliances in biosciences and advanced manufacturing. They would be supported by transportation systems linking the two metros. People and goods could travel back and forth via a widened Interstate 64, an improved U.S. 460, a high-speed train or a barge on the James River.

With the Port of Virginia in Hampton Roads serving as a global gateway and Richmond’s growing prominence as a logistics hub, Frantz believes both areas would benefit by touting their related synergies.

The idea isn’t entirely new. When Virginia Business began publication 30 years ago, there was talk of a Golden Crescent of prosperity in Virginia, arcing around the Chesapeake Bay from Washington, D.C., to Hampton Roads (see story on Page 43). At that time there wasn’t much development east of Richmond to Williamsburg. That has changed with new housing developments and businesses locating in New Kent and James City counties. So to many people, the idea makes more sense now.

Plus, there’s a sense of urgency. Virginia’s economy, hard hit by defense cuts, needs a boost. The Brookings Institution’s recent Metro Monitor Report ranked the Richmond region 59th economically among the top 100 in metro areas, while Hampton Roads was 97th. The rankings are based on job growth, gross regional product and aggregate wages from 2009 to 2014.

Overall, Virginia also is lagging. According to the U. S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the commonwealth saw virtually no growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) in 2014. Virginia ranked 48th among the 50 states, outperforming only Alaska and Mississippi.

The end of 2015 brought better news. Virginia reported 1.5 percent growth in nonfarm employment, compared to the year before, a bump that trailed a national increase of 1.9 percent.

To reverse the state’s sagging fortunes, Frantz, a Virginia Beach resident, is part of a well-coordinated mega-region push from Hampton Roads and Richmond business leaders. “We’re not talking about combining fire departments, school systems or any of that. We’re talking about marketing ourselves to the world as a larger, more diverse region that has many more assets.”

Picture this, he says: “You are sitting in a boardroom in Hong Kong, Paris or London, and you want to expand to the States. You can’t look at everything in the States, so you’re going to look at the top 20, 25 MSAs.”

According to the most recent population data, Hampton Roads ranks 37th in population among metro areas, with 1.7 million residents, while the Richmond area comes in 44th with 1.2 million. With those numbers, neither place would even get a look, says Frantz. “By combining and making us the 17th largest MSA, we’re going to be thought of in more boardrooms around the world as a candidate for expansion, especially since we have the global gateway to the mid-Atlantic in our port. With a [planned] 55-foot-deep channel, we will be the only port on the East Coast that will be able to handle the really big ships.”

Frantz sounds like a prophet of “The Metropolitan Revolution,” a 2013 book by Bruce Katz and Jennifer Bradley. While he shies away from that label, Frantz has read the book and agrees that metropolitan areas will be a driving force for economic growth and innovation. Or, as the book states, “places that link together grow together.”

Global gateways

Seventy-seven percent of the nation’s population and 80 percent of its economic growth are expected to occur in 11 global gateway regions between now and 2050.

The theory espoused in “The Metropolitan Revolution” is that large metropolitan areas will be dominant because they are more nimble than state and federal government bureaucracies, thus better able to solve problems. Think of Portland, Ore.’s sustainability initiative or Denver’s expansion of public transit. With overlapping networks of elected officials, heads of companies, universities and nonprofits already in place, metros can chart their destinies by collaborating and moving forward on concerns such as job creation, transportation and higher education — issues that get mired in the gridlock of Washington’s partisan politics.

The metro model has gained momentum since the Great Recession of 2007-09. Katz and Bradley refer to the economic downturn as a “brutal wake-up call” for cities and metropolitan areas because it drove home the realization that Uncle Sam can’t always come to the rescue.

Yet when one considers existing mega-regions — the population in the greater Atlanta area alone is 5.6 million — a Richmond-to-Hampton Roads region seems a bit small.

“We’re just in the early stages,” says Frantz. He expects it will take five years to get a political and public buy-in for a mega-region. Since there is no official process for designating a mega-region, it’s primarily a self-declared rebranding. In the meantime, supporters want to put up a website, create an umbrella organization and commission an economic impact study to support the idea. And that’s just the beginning.

The ultimate goal — after establishing patterns of inward and outward migration — would be to apply for the status of a Combined Statistical Area (CSA), which is an official designation from the U.S. Office of Planning and Budget.

There are 169 CSAs in the U.S. This federal designation, says Frantz, comes into play with many decision makers: when federal and state officials allocate public funding for infrastructure projects, companies make relocation and expansion decisions, professional sports teams select venues, and businesses spend advertising dollars.

Frantz saw evidence of this dynamic in 2013 when Virginia Beach dropped out of contention to woo the Sacramento Kings — an NBA basketball team. The city, which has a population of nearly half a million, represents the largest market in the country without a major league sports team. But Virginia Beach didn’t have an arena large enough to accommodate the Kings. Now plans have been approved for a privately owned facility seating more than 15,000 people.

Frantz says another problem in landing the Kings was a fragmented television market. “They looked at Richmond to the oceanfront as one market … They said it would have been critically important for them to come here to have one sports station covering the Richmond and Hampton Roads MSAs to help promote the team.”

Blurred lines

Mega-regions are made up of MSAs and CSAs. The lines blur as areas collaborate on issues. In the long-term, Frantz and his allies have their eyes on joining up with the Northeast Mega-region.

“This is where America is heading,” he says. “If you look at this map,” referring to a America 2050 map showing the country’s mega-regions (see page 40), you have a little circle here for Hampton Roads and a little circle there for Richmond.”

“What we can’t afford,” he continues, “what our kids and grandkids can’t afford, is for us to be two isolated islands in the middle of this highly connected economic juggernaut. We need to get together so that the Northeast Mega-region says, ‘You’ve got to be part of us, we need you,’ because of all of the product coming in and out of the port flowing through Richmond and then to the North and South.”

The groups meet quarterly. At last fall’s gathering, they agreed on a list of initiatives to support during this year’s General Assembly. After successfully lobbying for the widening of Interstate 64 last year, from Highway 199 in Williamsburg to the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel, the groups are supporting these goals in 2016: $350 million in funding for infrastructure improvements at the Port of Virginia; $39 million in funding for GO Virginia, a program that would provide state funds to localities that collaborate on economic development and government efficiency projects; and the continued widening of I-64, from 199 to the 295 bypass at Richmond.

More than a numbers game

Becoming a mega-region is more than a numbers game. Robert Puentes, a director of the Metropolitan Infrastructure Initiative and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, says, “It’s fine as a component to a robust economic strategy, but combining into a CSA solely is not the answer.”

To him, there are more pressing issues. “[Virginia] is heavily reliant on military spending. That’s going its own way. It’s more important to recognize what the region does well and focus in on that … Equip the residents and the workers in those places to compete for the jobs of the next century. If you do all that — the basic stuff — then you can think about joining up the MSAs for marketing and branding reasons.”

Eugene Trani takes much the same view. Trani, the president emeritus of Virginia Commonwealth University, is credited with expanding VCU’s role as an economic development engine during his tenure. He now leads Richmond’s Future, an independent think tank that has been studying the future of the region since 2011. The group released a report in February that discusses the best path forward for economic growth.

It did not recommend a mega-region. “We have come to the conclusion not to adopt the mega-region but to focus on regional strategies between the Richmond metro area and Hampton Roads in the area of logistics,” says Trani. Between the ports in Hampton Roads and the Richmond port, now under the management of the Virginia Port Authority, “we see a major opportunity for cooperation.” A mega-region approach may be appropriate further down the road, Trani adds, and it should include a focus on the area’s higher education assets.

While the areas share commonalities, there also are differences. Bob Holsworth, who worked for Trani at VCU and served as research director on the Richmond’s Future project, notes some of these differences. “One is educational attainment,” he says, with the Richmond metro area having a higher percentage of people with college degrees.

“Another big difference is the traffic situation. And, so at least in the moment, there are probably not too many people in those regions who think of Richmond and Hampton Roads as inextricably linked. Those are the challenges they face, and that’s why they need some clear victories that demonstrate that collaboration between the two areas improves the quality of life for everyone and the economic opportunity as well.”

A new 40-year lease on Richmond’s port held by the state’s port authority is expected to spark economic opportunities for the city as well as Hampton Roads. The Richmond Marine Terminal is located on the James River, just off I-95 with access to rail and barge service. With $17 million in upgrades planned, business leaders hope that the port will be a magnet for companies that need to move cargo. Plus, it will be better equipped to offload containers coming to Richmond by barge on the James River from Hampton Roads.

The barge service “takes the wear and tear off I-64 [from container truck traffic], and it’s more economical to move the goods by barge to Richmond. We all benefit,” says Chandler of New Richmond Ventures.

With a central East Coast location — about a two days’ drive from most of the country’s population centers — Richmond already has attracted several large distribution centers including Amazon.com, and Republic National Distributing Co., the second-largest wine and spirits wholesaler in the U.S.

While the ports play a crucial role in attracting logistics companies, they also provide “an efficient link to the global supply chain,” says Reinhart. Since taking the helm two years ago as the Virginia Port Authority’s executive director, he has insisted on marketing the state’s six port terminals — four in Hampton Roads, the inland port at Front Royal, and the Richmond terminal — as a single entity. As for a mega-region, he supports the vision. “From a business perspective, it makes all the sense in the world, because in the global marketplace, you need to have relevance, and the strength of two market regions starts to move us up that scale of relevance.”

Combining the two metros “gives us more to talk about — a larger population base, a larger workforce,” adds Reinhart. A mega-region would support more infrastructure improvements at the ports, which he says would create new jobs in construction, logistics and advanced manufacturing. In the past two years, says Reinhart, “we’ve had 75 businesses locate to Virginia because of the port, and our volumes have continued to go up.”

Hampton Roads is home to the third-largest container port on the East Coast in terms of cargo volume and has the deepest channel at 50 feet. Plans to further deepen the harbor to 55 feet will give it a competitive edge in an era of supersize ships. In fiscal 2013, the port generated $60.3 billion in port-related spending on goods and services. However the port’s total economic impact that year, including the movement of bulk goods and containerized cargo, was $88.4 billion, according to a study by the Mason School of Business at the College of William and Mary. The larger figure represented 10 percent of the state’s GSP (gross state product).

Lou Haddad, CEO of Armada Hoffler Properties Inc. in Virginia Beach and a member of the Hampton Roads Business Roundtable, is another mega-region fan. “As a relatively small public company listed on the New York stock exchange, we see a lot of investors. We’re not on the radar screen of the vast majority of them, and it’s because of an unfamiliarity with our market,” he says. “A mega-region would be a tremendous boon to commercial real estate simply for the fact that it would enable us to play on a lot bigger stage.”

A new voting coalition?

In addition to linkage on economic growth issues, the business roundtables see the potential for creating a powerful voting coalition among the metro areas’ legislators in the General Assembly.

“Once you start thinking about the common interests between Richmond and Hampton Roads, then you begin to pull your political influence to get things accomplished …,” says Chandler.

One mega-region expert, Hunter Morrison, says it’s better to stick with the business case. “Politicians are elected by constituents and will protect their constituency. Even if they want to be broad minded, that’s not what they get paid to do.”

Morrison is director of the Northeast Ohio Sustainable Communities Consortium (NEOSCC) and the architect behind an award-winning comprehensive plan for the future for Northeast Ohio, (Cleveland-Akron, Canton-Youngstown), a 12-county project.

He advises business leaders to figure out “how things work and how to make things work better.” The way to start is with an attitude: “If you want to become a region, you have to start acting like one.” Start thinking along the lines, he says, of “we’re a place with shared values, a shared economy and shared opportunity.”

Getting people to think of a geographic area as one place can be daunting, and Morrison says it’s unlikely to happen in less than a generation. Where leaders can get a buy-in is across a common mental map. “Like the Research Triangle [in Raleigh-Durham] became a place in people’s minds. Silicon Valley is a place in people’s minds even if they’ve never been there.”

In the early stages, Morrison says he would target young people. Millennials have grown up with technology like Google Earth, and “they think about things a lot differently than their mothers and fathers … I see this in our state leaders in their 30s, they don’t get this parochial stuff,” he says.

In other words, they’re all about connectivity. In December, Frantz took his case to Thrive, a program for young professionals ages 21 to 39, that’s sponsored by the Hampton Roads Chamber of Commerce. Julia Rust, an attorney with Pierce/McCoy in downtown Norfolk and the group’s chair, says, “Everyone seemed enthusiastic about it. It makes a lot of sense from a young professional’s perspective because it would create more opportunities for growth, mobility and the quality of life millennials are looking for.”

Frantz agrees that a mega-region is “really about the next generation of leaders.” And he hopes they are getting the message. “The same old ways we’ve done things will not work. We need to think boldly, positively and figure out how to combine our strengths so we can succeed in the new economy.”

-